‘They were trying to exorcise something’: How five filmmaking titans were changed by World War II

June 15, 2017 By Michael Ordona, LA Times

Largely lost in the legends of five of Hollywood’s most accomplished filmmakers is how they all served during World War II — and how that experience influenced their art.

“I think we forget that the true filmmakers are influenced by life,” says “Five Came Back” director Laurent Bouzereau. “When you re-watch [the movies they made after the war], you see them in a different light: ’My God, they were talking about themselves,’ or ”They were trying to exorcise something.’”

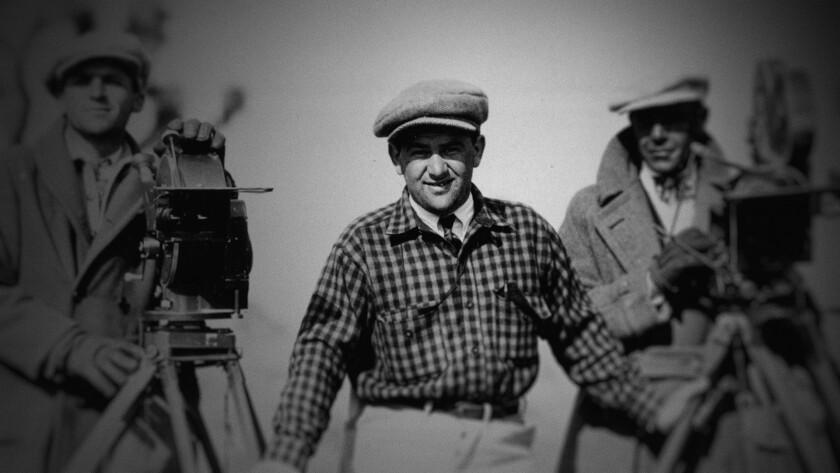

Frank Capra (“It’s a Wonderful Life”), John Ford (“The Grapes of Wrath”), John Huston (“The Treasure of the Sierra Madre”), George Stevens (“Giant”) and William Wyler (“Ben-Hur”) each joined the government’s propaganda program, putting massively successful commercial careers on hold to make message films at home — or documentaries shot on location in war zones.

Film journalist Mark Harris’ book about their service and the aftermath, “Five Came Back: A Story of Hollywood and the Second World War,” was a finalist in 2015 for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for History. It is now a three-part Netflix documentary, with Bouzereau recruiting five of today’s best-known filmmakers for running commentary, and Meryl Streep to narrate.

“Five” producer Steven Spielberg discusses Wyler’s journey. Francis Ford Coppola takes on Huston; Paul Greengrass, Ford; Guillermo del Toro, Capra; and Lawrence Kasdan follows Stevens’ fascinating trek.

Bouzereau says the commentators were chosen largely because they matched up with their subject filmmakers in some way. For instance, he aligns Coppola’s “Making ‘Apocalypse Now’ was my war” mind-set with Huston’s hunting of elephants while making “The African Queen”: “Those are people who lived the filmmaking experience to a degree that is almost beyond what one can imagine.”

Despite this Hemingway-like, adventurer‘s approach, when Huston’s documentary work was criticized as “anti-war” by Army officials, he reportedly responded, “Well, sir, whenever I make a film that’s for war, you can take me out and shoot me.”

While Huston’s “The Battle of San Pietro,” presented as a you-are-there chronicle of an actual firefight, included some staged footage, Bouzereau says there’s a kind of cinematic redemption in his painfully honest documentary, “Let There Be Light,” a portrait of post-traumatic stress disorder before it had a name.

“There’s this scene with this African American [veteran]; they say something to him, and he says, ‘Well, I hope so, sir, I hope I’m going to be OK.’ And he takes off his glasses and wipes his tears. That clip gets me each time,” says Bouzereau. “There’s something so real about that moment. It summarizes everything.”

Ford, one of the inventors of the macho western genre, put life and limb on the line to make “The Battle of Midway,” a documentary shot under actual fire from Japanese planes.

Bouzereau says, “When Ford is at Midway, on top of a platform as the bombs are dropping to get a shot, I’m thinking, ‘Greengrass would probably do the same thing.’”

Del Toro evokes his own and Capra’s immigrant experiences in discussing the life and work of one of the leaders of the cinematic war effort. Bouzereau says, “Nothing prepared me for the brilliant, emotional interview we did together. Everyone who came to that interview was riveted.”

In part because of a meeting he had with Wyler early in his career, Spielberg chose to discuss him. After the war, Wyler made “The Best Years of Our Lives,” a decidedly untidy look at the struggles of veterans returning home. Among its Oscars were awards for best picture and Wyler’s second directing honor (of three).

Stevens, until the war known as a master craftsman of slick comedies and musicals, made you-are-there documentaries in the European theater. His cameras were the first to capture the death camp at Dachau.

Bouzereau says Stevens’ Dachau footage “is no longer shot with a point of view, but with the goal of being evidence. It was used, of course, at the Nuremberg trials. He grabbed the camera himself; he doesn’t let anyone else do it.”

When he returned, the filmmaker showed little interest in his former genres.

After a long layoff, Stevens “worked on developing a comedy with Ingrid Bergman and eventually had to give it up: ‘I just can’t.’ Then you look at movies like ‘Giant’ — there’s an incredible shot where the character Sal Mineo played has been killed during the war and there’s this shot of a train stopping, and the train leaves, and there’s his coffin.”