Review: ‘Five Came Back’ shows how World War II changed prominent directors of Hollywood’s Golden Age — and changed film history

March 30, 2017 By Kenneth Turan, LA Times

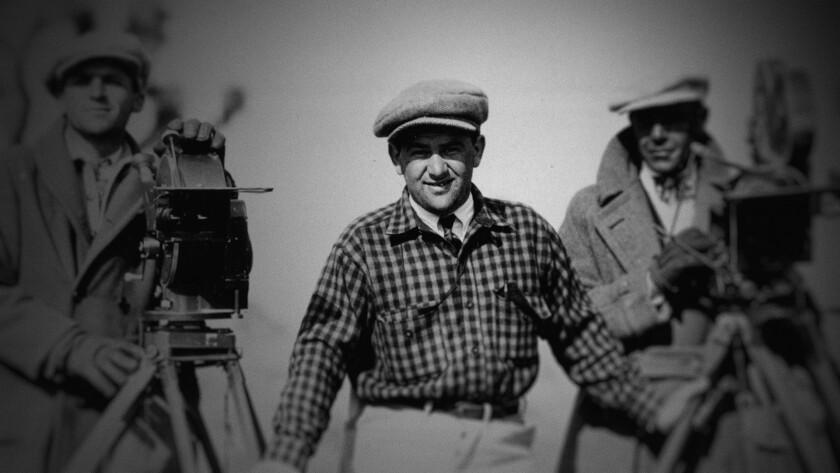

Hollywood’s directors weren’t always boyish figures who looked good in baseball caps. Once upon a time they were full-fledged adults whose life experiences included the darkest sides of human nature, and none more so than the filmmakers featured in the exceptional documentary “Five Came Back.”

That handful of individuals — Frank Capra, John Ford, John Huston, George Stevens and William Wyler — were some of the greatest names of Hollywood’s Golden Age. Yet they all unhesitatingly abandoned their careers at the start of World War II in order to work for the common good, an action that changed their lives, and their films, forever.

“Five Came Back,” directed by documentary veteran Laurent Bouzereau and written by Mark Harris based on his bestselling book, is a compelling examination of this little-known period of Hollywood history, a great subject that gets its full due here.

Available on Netflix and opening for a one-week Oscar-qualifying run at Laemmle’s Monica in Santa Monica, the three-hour-plus documentary is thorough, thoughtful and authoritative, an experience that honors the multiple complexities of this situation and, best of all, helps us feel what these directors felt as they went forward into what was very much terra incognita.

Nothing if not meticulous, the filmmakers plowed through over 100 hours of archival and newsreel footage, including candid late-career interviews plus 30 more hours of outtakes and raw footage, not to mention the more than 40 wartime documentaries and training films these directors had a hand in.

(As a bonus for Netflix viewers, 13 of the best of these docs, including Ford’s “The Battle of Midway,” Huston’s “Let There Be Light” and Wyler’s “The Memphis Belle,” will be available on the streaming service.)

More unexpected — and unexpectedly effective — is the filmmakers’ decision to pair the five who came back with significant contemporary directors who serve as kind of spirit guides for modern audiences for whom WW II might seem as distant as the Peloponnesian War.

So Guillermo del Toro talks extensively about Capra, a director who’s made him cry more than any other, Francis Ford Coppola analyzes Huston, Paul Greengrass does likewise with Ford, Lawrence Kasdan looks over Stevens and Steven Spielberg describes Wyler as a director focused not on artistic statement but on “helping tell the story better.”

“Five Came Back” begins by positioning each of its directors in the prewar movie world. Wyler, for instance, was seen as a perfectionist known as “40-take Willie,” while Stevens was a specialist in light entertainment who wanted to expand his range. Capra was an immigrant from Sicily who, in Del Toro’s words, always felt “the need to be loved,” while Greengrass sees Ford’s character as a clash between the rebel outsider and a pillar of rectitude.

Each of these directors came to their war work in their own way and their own time. Capra, though a conservative Republican, was wowed by a meeting with Franklin D. Roosevelt and agreed to be the head of the “Why We Fight” series that was to explain war aims to the troops.

Ford was the first to see combat, which resulted in 1942’s influential “The Battle of Midway.” “Reality comes to him,” is how Greengrass phrases it, “and he rises to meet it.”

Wyler, for his part, hit his stride with 1944’s “The Memphis Belle: A Story of a Flying Fortress.” Detailing the plane’s 25th and potentially final flying mission, it proved to be gripping viewing (“one of the most stunning things I’ve ever seen,” Spielberg says of one of its sequences) and was the first film to be reviewed on the front page of the New York Times.

Huston, as befits his rebel image, was always getting into trouble with his military bosses. His 1946 “Let Their Be Light,” the first cinematic treatment of what we now call post-traumatic stress disorder, was so controversial it wasn’t shown publicly for 35 years.

Perhaps no director had a more unexpected trajectory than light comedy specialist Stevens, who was, along with Ford, in charge of photographing D-day. He stayed with American troops for seven months as they fought across Europe, and ended up being one of the first Americans into Dachau, and the color footage he shot was a key exhibit in the Nuremburg war crimes trials.

After the war, picking up careers in an indifferent Hollywood was hard for everyone. Capra’s darker-than-usual “It’s a Wonderful Life” in effect ended his career, and Stevens, changed forever by his concentration camp experience, abandoned light comedy for dramas like “A Place in the Sun,” “Shane” and “Giant.”

Most dramatic of all Wyler, after losing 80% of his hearing in an aircraft, went on to make the multi-Oscar winning “The Best Years of Our Lives,” a classic treatment of soldiers returning home. Spielberg says he’s watched it at least once a year for 30 years, and the gift of “Five Came Back” is that it allows us to understand the passion and commitment that made Wyler and his four comrades do what they so passionately did.